speed. A calculator is available at www.marksmarine.com.

You can get an idea of the needed pitch if you know your

boat’s speed and engine rpm. As an example assume the

boat goes 60 mph and the propeller turns 16,000 rpm. The

boat is traveling 60x5280/3600 or 88 feet per second.

That’s 88x12 or 1056 inches per second. The propeller is

turning 16000/60 or 266.7 revolutions per second so it

needs to advance 1056/266.7 or 3.96 inches per revolution.

If there’s 10% slip that means the prop will only go 90% as

far each revolution as the measured pitch. That means the

prop needs a pitch of 3.96/.9 or 4.4 inches. With that

information you can look at the various tables that show

prop pitches and select a prop.

Most companies list props with a diameter and pitch to

diameter ratio. Thus an Octura X470 has a 70 mm diameter

and a pitch 1.4 times that or 98 mm. Dividing the metric

dimensions by the 25.4 millimeters in an inch gives 2.76

inches diameter and 3.86 inches pitch. The new ABC props

use inch measurements so an ABC 2715 has a diameter of

2.7 inches and a pitch of 1.5 x 2.7 or 4.05 inches. Our 60

mph boat might need a little more pitch.

What about the diameter? Since there’s no engineering

information on model props, you need to rely on

experience. The pitch of a prop won’t change if you change

the diameter, so if the prop bogs the engine down or draws

too much current, a small reduction in diameter will help.

Look at the equations in the beginning and realize that the

torque varies as the fifth power of the diameter.

Of course there are a lot of other changes you can make

to match a prop to your boat and get the best speed. We will

cover all that in the next part in the April 2014

Propwash

.

PROPWASH

October 2013

27

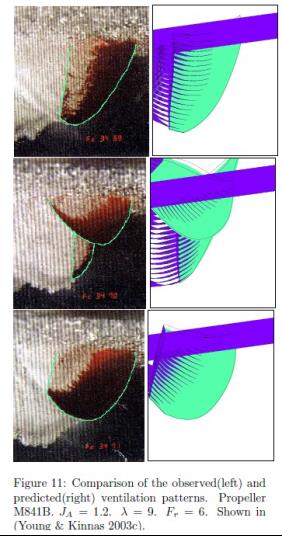

All these considerations have made theoretical analysis of surface

piercing props difficult. This hasn’t stopped either full size or model

boat racers. When an early boater noticed his boat went faster with

the prop partially out of the water, the race was on. One of the first

well known examples was Rainbow IV in 1924. Since that time

nearly all the racing development has been by trial and error. This is

especially true for model props. It’s easier and probably more

accurate to try a number of props then to try to calculate what should

work.

However, a little basic prop math will help. The most important

mathematical relationship to understand is the relation of pitch to